Increasingly, Evangelical Anglicans are finding it difficult to remain within the Church of England.

Now, as a Dissenter, you will hardly be surprised that I think they should all leave. But I don’t think those who are convinced of Anglicanism should necessarily leave their faithful Anglican communions. I may not be convinced of their ecclesiology and praxis, but if you are – and your church holds to the gospel – I wouldn’t expect you to leave. But the Church of England, however, is a different matter. Here are five reasons I think it is untenable for genuine believers to remain.

Fellowship with false teachers

It is well known that the Church of England is broad. Some actively tout that as one of its strengths. But the reality is that those who believe the gospel of Jesus Christ are repeatedly warned in Scripture to have nothing to do with those who peddle a false gospel (cf. Rom. 16:17; 2 John 10–11). It is hard to see how remaining in the same denomination as such people – actively affiliating ourselves to the same groupings to which they are welcomed – demonstrates any sense whatsoever of the separateness to which the Lord calls us.

Whilst Paul insists that those who persist in sin should be put out from among us, many actively take their parishioners to meetings knowing that at them such false teachers will be delivering talks. They attend groups and meetings with those who clearly preach a gospel entirely contrary to the one they claim to believe. How do we justify this in light of what the Bible tells us regarding the fellowship of darkness and light?

Submission to false teachers

Similarly, there is no getting away from the fact that episcopalianism is hierarchical. You take your orders from a bishop who has a say over your church and submit to suffragan bishops underneath them. For example, the Archbishop of York – who originally supported Jeffrey John in his bid to become Bishop of Reading and whose views on the issues surrounding that controversial application remain unchanged and well-known – sits in the second-most important post in the Church of England to whom many others answer. At some point, Evangelicals must admit they are ultimately in submission to those who would reject the gospel of Christ.

Some, of course, try to get around this by submitting to flying bishops or those outside of their area. It is hard to see how this, realistically, upholds the principles of episcopalianism and isn’t something of a fudge. But, that aside, it doesn’t get around the fact that those bishops coming into your diocese remain under the authority of the selfsame bishops you are seeking to avoid. The Bishop of Maidstone, under whom many conservative evangelicals place themselves, still acts under the authority of the diocesan bishop in whatever diocese he works. If you have placed yourself under his authority, but he is still answerable to your diocesan bishop, in what way have you resolved the original issue?

Propagation of false teaching

Even if it is denied that Evangelicals submit to such false teaching, it is quite clear that those in authority continue to appoint to important positions those who deny important doctrines. This, minimally, suggests they see no problem with such things or, worse, actively endorse them. For example, there is the appointment of the Archbishop of York. However, there is also the appointment of The Revd John Shepherd to the Anglican Centre in Rome, a man who denies the bodily resurrection of Jesus. Those responsible for the appointments are, therefore, actively propagating such false teaching. These are the same people to whom Evangelicals are submitting by remaining within this denomination.

Changes to doctrine

Many wish to avoid the above points altogether and insist, just because some people in the church hold errant views is no reason to leave it. While the church holds to the Thirty-nine Articles and its official doctrine remains sound, they will remain.

Whilst that sounds noble, in reality, the teaching and practice of the church has changed. The introduction of transgender liturgies and same-sex blessings, though the church may still insist that it holds to the Thirty-nine Articles and they haven’t changed, make clear that praxis has overtaken. I can insist that I still hold to my church constitution all I like, but if everything I do within my building departs from what is written there, it is little more than empty words. The fact is, doctrine has changed. It has been changing for some time.

Whilst the constitution may still be sound, the leadership is neither willing to implement it nor to discipline those who depart from it. It actively allows – even encourages – practice that would depart from the gospel. The Evangelicals have repeatedly drawn their red lines that have been repeatedly ignored and they have repeatedly backed down. To stay is to accept that doctrine has, in reality, changed.

A question of faithfulness

I have written previously about how the fundamental job of the church, and of Christian people, is to be faithful to Christ. The question Evangelical Anglicans need to seriously ask is this: can I realistically be faithful here?

Lee Gatiss, of the CofE’s Church Society, will respond to this article next month.

Stephen Kneale

Stephen Kneale is the Minister of Oldham Bethel Church and he blogs at www.stephenkneale.com

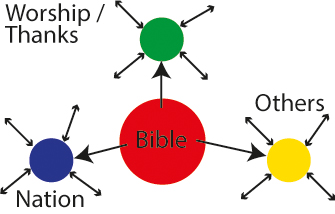

It can be good to start by thinking in terms of three one-hour slots. Use an A4 sheet of paper. In preparing, select a few verses or a passage of Scripture which will act as your compass for the day. You can focus your thoughts around those verses and keep coming back to them if your mind wanders. At the centre of the A4 sheet draw a fairly big circle and copy your verses into it.

It can be good to start by thinking in terms of three one-hour slots. Use an A4 sheet of paper. In preparing, select a few verses or a passage of Scripture which will act as your compass for the day. You can focus your thoughts around those verses and keep coming back to them if your mind wanders. At the centre of the A4 sheet draw a fairly big circle and copy your verses into it.